Everything we’ve been discussing so far was related to translating the interface only. That is – the hard-coded strings. But that’s not the only part of a website. Arguably, it’s not even the largest one. The other side of this coin is content. This includes:

- post content and titles,

- post slugs,

- custom field values (metadata),

- taxonomies names and descriptions,

- options (like our alternative “Reading time”),

- and more…

I’m going to tell you something disturbing, so make sure you’re sitting down. WordPress does not currently provide a native way of translating content. Content translation is achieved only with plugins. As a matter of fact, localizing content stored in the database is such an enormous undertaking that translation plugins are one of the most complex plugins in the entire WordPress ecosystem.

There are 5 types of translation plugins, each working in a different way. We’ll cover them one by one, along with their pros and cons.

1. Separate Post Per Language

This family of plugins is the most popular one, and for good reasons. The two biggest players in this category are WPML and Polylang.

It is arguably the most natural way of structuring translations. Every translation is a separate post with its own content. If you have an English and a Polish version of your site, you will have 2 different posts – one English and one Polish. Each post has its own row in the database, its own ID, its own URL, its own metadata, etc.

These plugins look at the URL and hook into different parts of WordPress. For example, if the path starts with /pl/, a plugin might filter every WP_Query call to make sure only translated posts are returned. It obviously also filters the global $locale variable to load the appropriate MO/PHP/JSON files for plugin and theme translations.

You can see the advice to use WordPress standard APIs shines again. If you were to, for example, use $wpdb directly instead of using WP_Query, these plugins wouldn’t work as expected. Furthermore, plugins like that rely heavily on custom database tables. There’s only so much you can reasonably achieve with WordPress’s default schema. They usually also provide some kind of string translation.

Think about our alternative “Reading text” option in wp_options. That’s not a post, so it’s not as obvious how to make it translatable. To achieve that, usually a wpml-config.xml file is used. Yes, that’s a format created by the WPML plugin, which has been around since 2007. It’s become a de facto standard. Here’s the content of this file required to make our option translatable:

<wpml-config>

<admin-texts>

<key name="pgn_reading_time_text"></key>

</admin-texts>

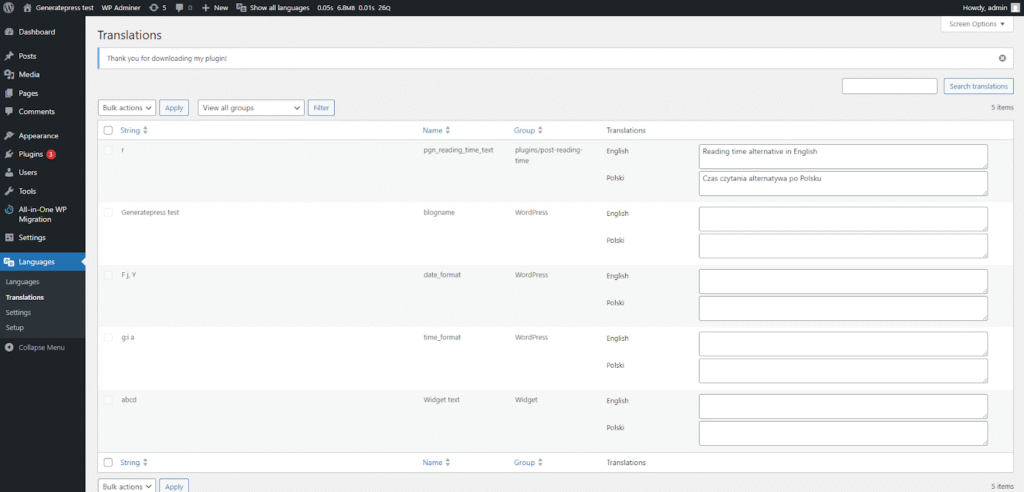

</wpml-config>That informs these plugins that they should hook into every get_option() call with this key and filter its output with the translated version. It’s the plugin/theme author’s responsibility to provide this file in their root directory. It’s used for many more things than just options, and you should read the wpml-config.xml documentation for more info. Here’s what the translation interface for our option looks like in Polylang:

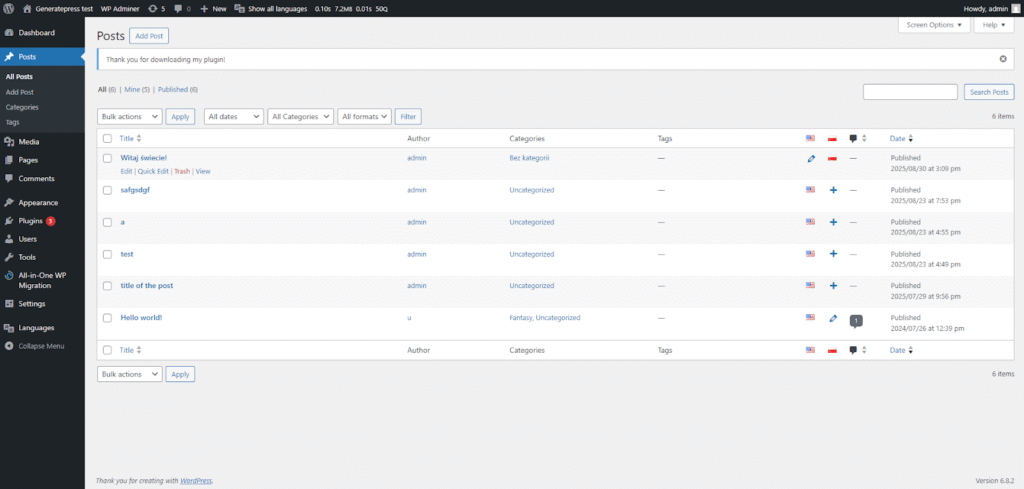

And here is what the “Posts” menu looks like with Polylang. Notice the buttons to add/edit versions for each active language:

Pros

The pros of this architecture are that it’s mostly native to WordPress’s data model and usually provides good SEO control (unique URLs per language). It also has broad ecosystem support, as it depends on standard WP APIs. It’s less invasive into the way WordPress works, which can prove very beneficial, especially considering compatibility with other plugins.

Cons

The biggest cons are related to the increased size of the database. You will have twice as many entries in many of your tables. The custom tables add additional complexity to the database schema.

In my opinion, this family of plugins is ideal for 95% of websites. It provides a perfect balance between simplicity of use and compatibility with WordPress. It’s easy to understand and the effects of the increased database size are usually negligible.

2. String-Level Translation

Probably the next most common type of translation plugin is the “single page, string-level translation” plugin. The prime example is TranslatePress.

Plugins like that do not create separate posts for different language versions. They scan the content of the entire page and provide a proprietary frontend editor for translating what you see. It’s a little hard to explain in words so take a look at TranslatePress’s UI:

You can see that we are not translating the content in the editor, but while looking at it on the frontend. You can click on every string you see on the screen and translate it in the panel on the left. The translations are not stored as the entire content of a post. Instead, every singular identified string (a paragraph, a variable, etc.) gets its own row in the database.

All of the translations are stored in custom tables. The plugin hooks into the content while it’s being displayed and swaps original strings for translations. There’s no such thing as filtering the WP_Query to display only the translated posts, as there is only ever one post in the database. By default, everything is displayed, whether it is translated or not (you can manually exclude posts and pages from being displayed on certain language versions).

Pros

Plugins like WPML and Polylang are more intuitive for us as developers (at least they are for me). Their data model makes sense. Plugins like TranslatePress are more intuitive for normal people who do not understand how WordPress or databases work. They see the entire page and they can change it right there, on the frontend. It’s natural, easy, and responsive. That is the biggest advantage of this type of solution – ease of use for non-technical people.

Cons

Unfortunately, the downsides are pretty stark, especially for larger or more advanced websites. Translations are fragile, as they are key-value pairs. If you change the original text, even by adding a comma, the key changes, and the translation gets invalidated. It’s also harder to manage string-level translations for websites with hundreds/thousands of pages.

Another problem is compatibility. WPML and Polylang played nicely with the native WordPress way, but TranslatePress is more “hacky” – replacing strings in the rendered HTML. Let’s say you have an SEO plugin. How will you make it work separately for the English and the Polish post? You can’t because there’s only one post in the database. This solution is overall more likely to be problematic and incompatible with other plugins.

It’s also my assumption that TranslatePress is slower than “separate posts” plugins, as it requires additional computation to handle string replacement. I haven’t conducted any tests on that though, so don’t take my word for it.

What definitely is true is limited flexibility for different content per language. What I mean is not only simple translations, but possibly even separate layouts for different languages. Unlike with Polylang, you can’t achieve that with TranslatePress. You are tied to string translations only. It’s also harder to migrate TranslatePress translations to a different translation plugin.

That’s 4 paragraphs for the downsides only, and you could definitely come up with a few more if you spent some time thinking about it. To be clear, I’m not totally against TranslatePress. Plugins like that work well for small to medium sites with no advanced needs, and when you need a live visual editor. Just keep in mind all of the above when making that decision.

3. SaaS Translation Proxy

There are solutions which are completely detached from WordPress. Some of the examples are Weglot and GTranslate. Instead of storing the translations in your website’s database, they are stored on their servers.

The basic mode of operation is that either your website becomes a reverse proxy for the translation server, or the translation server becomes a reverse proxy for your website. Either way, every request to a translated page has to go through an additional network node – the server storing the translations.

Solutions like that tend to be CMS agnostic. They don’t have to care if you’re using WordPress or not because they don’t interact with it. They only replace strings in the final rendered HTML. Kind of like TranslatePress, except even later in the lifecycle of the page.

They provide a frontend editing UI – very similar to the one you just saw with TranslatePress. They are usually more flexible, allowing you to modify even the raw HTML. The translations don’t live in your admin dashboard, they live in the SaaS panel.

Pros

One of the biggest upsides of solutions like that is the fact that they tend to have significant support for automatic translations. TranslatePress supports automatic translations as well, but they are more embedded into the way these SaaS products work.

For example, GTranslate offers unlimited automatic translations without any additional charge. This can be a very important factor for certain kinds of websites. Imagine you have a website with a few thousand posts that get updated daily using an external API that doesn’t provide translations. An automatic translation service is really your only option.

Cons

Having worked with GTranslate on such a website, let me tell you from experience – do not go this route unless you absolutely have to. Most of the TranslatePress downsides are also relevant to translation proxies.

On top of that, there are many more problems. The ongoing costs for SaaS products are usually much higher. There’s limited control over what you can actually do in these panels. A lot of the time it doesn’t work correctly. A number is substituted in the wrong place because a translated version uses a comma instead of a period, which makes your house price be $50 and the size be 500,000 m2.

It’s completely detached from your website. The biggest problem with that which nobody mentions is the fact that these solutions usually do not filter the global $locale in WordPress. This means that your plugins’ and theme’s l10n files will not be used! Your website will always be rendered in English and only translated by the SaaS. Your WordPress website has no idea there exists any translated version.

A huge problem stemming from that is JavaScript translations. If your JS renders any content on the page, this content is only rendered in the client’s browser. It is not a part of the HTML returned by your server, which means that the translation proxy does not see it. Couple that with the fact that l10n JSON files aren’t loaded, and you’ve got a recipe for disaster. It is a nightmare trying to translate JavaScript-added strings using services like that.

Oh, and did I mention that the translations aren’t stored on your server, but instead on the service provider’s server? Well, good luck pitching that idea to your lawyers, especially if you’re in an industry handling sensitive personal data.

4. Separate Sites Per Language

There is one plugin that doesn’t fit into any of the previous categories, and that’s MultilingualPress. I’m not going to explain it in detail, because it’s based on technology we haven’t discussed yet (we will later). This technology is WordPress Multisite.

The basic idea is that each language version is a separate WordPress instance. A completely detached website in the same Multisite network. It provides unlimited freedom per locale (different themes, plugins, content, etc.). It’s mostly fit for large sites and organizations, especially if a separate team handles each language version.

It’s more work to manage and set it up. Cross-site syncing is more complicated. Generally speaking – for 99% of websites, it’s like using a sledgehammer to crack a nut.

5. In-Content Markup (Legacy)

This last one is really more a fun fact than a useful translation architecture. It’s a legacy system used by an old and abandoned qTranslate-X plugin (and its still supported community fork – qTranslate-XT). It provided string-level translations, but stored them in the post’s content instead of in separate tables. The content might’ve looked like this:

[:en]Hello[:pl]Witaj[:]

You can imagine why this solution was so problematic. It uses the post_content column in a way it was never intended to be used. What if a plugin hooks somewhere to read or modify the content before qTranslate-X gets to parse it? It’s a brittle solution. Don’t use it.