It’d be a shame if you created a great theme or developed an amazing plugin but only English speakers could use it. Internationalization (i18n) and localization (l10n) are required for your strings to be translated into multiple languages.

Let’s start by clearing up those 2 terms:

- i18n is the practice of making your code translatable.

- l10n is the practice of translating the code. You (or more likely a translator) are manually translating every hard-coded string.

WordPress uses the GNU gettext system. As such, there are many commonalities. Translatable strings have to be wrapped in a special internationalization function. The code is then parsed and a .pot (Portable Object Template) file is generated. This file is the template to .po (Portable Object) files, which contain the final translations. These .po files are then compiled into optimized .mo (Machine Object) files, which are used by WordPress to serve translated strings.

Don’t worry if you don’t get it yet. You will by the end of this chapter. Let’s get into the details.

i18n In PHP

There are a few essential internationalization functions you have to know:

- __()

- _e()

- _n()

- _x()

__( $text, $domain ) is the fundamental “return translated string” function. Here’s how to use it:

$translated = __( 'String to translate', 'post-reading-time' );The first parameter is the string to be translated, that’s obvious. But what’s the second one? Well, that’s the text domain. The text domain ensures the translations of your theme or plugin don’t get mixed with another theme or plugin. How else would WordPress know which translation file to use if two plugins contained the same string? It’s the unique identifier for all your internationalized strings.

The text domain has to always be passed as a literal string. It can’t be a variable. That’s because this code is later statically parsed to generate the translation file.

_e( $text, $domain ) is an alias to “echo __( $text, domain )”. It echoes the translated string instead of returning it.

_x( $text, $context, $domain ) is a translation function used when you need to add context to the string. An example of when that’s useful is for words which can serve both as a verb or a noun. The second argument becomes the context, e.g.:

$translated = _x( 'Post', 'noun', 'post-reading-time' );This will create a separate translation entry from the word “Post” with the context “verb”. This way, the translator can translate them separately, as most languages will have different words for them. There’s also an _ex() version of this function. It echoes the string instead of returning it.

_n( $single, $plural, $number, $domain ) is for strings containing variable numbers. Different languages have different rules when it comes to singular and plural numbers. Just think about “1 post, 2 posts”. These rules get way more messy for different languages, and we’ll get to that in a moment. Here’s a usage example:

$translated = _n( '%s comment', '%s comments', $count, 'post-reading-time' );If $count is equal to 1, the first string will be returned. If it’s greater than 1, the second one will be returned. Note that the %s placeholder will not be replaced with $count. It’s the developer’s responsibility to do that later (probably using printf).

Some niche cases require context for strings containing numbers. Thankfully, there’s a function for that:

_nx( $single, $plural, $number, $context, $domain ). This works just like _x(). Its most important utility is for disambiguating homonyms:

$soccer_matches = _nx( '%s match', '%s matches', $n, 'soccer games', 'post-reading-time' );

$wooden_matches = _nx( '%s match', '%s matches', $m, 'matchsticks', 'post-reading-time' );Unfortunately, there are no _en() or _exn(), so you’ll have to echo the outputs yourself.

Dates & Numbers

There are 3 special situational functions:

- date_i18n()

- wp_date()

- number_format_i18n()

date_i18n() is an obsolete function used to internationalize a date in a given format. Its job is translating strings like the weekday and month names. This function is a little confusing so please read its documentation if you ever have to use it.

Why did I say it was obsolete? Because it got superseded by wp_date() in WordPress 5.3. The old function was quirky and problematic, namely – you had to take care of offsetting the timestamp to match your timezone.

date_i18n() does not care about your site’s timezone. It only translates whatever date you give it. If your site’s timezone was Europe/Warsaw, you’d have to manually offset the timestamp by 1 hour for winter time (UTC+1), and by 2 hours for summer time (UTC+2). As you might imagine – that’s brittle.

wp_date() takes care of that for you. It expects a UTC timestamp and a separate timezone argument (defaults to the site-wide timezone specified in settings). It’s DST aware (winter vs summer time) and just as date_i18n(), it takes care of string translations. You should always use wp_date() when dealing with dates in WordPress.

number_format_i18n( float $number, int $decimals ) formats a float number based on the locale. It returns a string. Different regions have different standards when it comes to numbers. Some use periods, some use commas, and some use spaces. Here’s an example:

$num = number_format_i18n( 1254.5, 2 );$num will equal “1,254.50” for US English and “1 254,50” for Polish.

Variables

What do you do if you have a variable in the string, like “Your city is $city”? You can’t just use this string inside an i18n function. If you did that, the translator would translate its static version (“Your city is $city”). But then during the code’s execution, it’d become “”Your city is London”, which would have no matching translations.

The correct way is to use printf (or sprintf), usually with a helpful comment:

printf(

/* translators: %s: Name of a city */

__( 'Your city is %s.', 'my-plugin' ),

$city

);The string to be translated is just a static string with a %s placeholder. The comment is optional, but it can be a helpful hint for translators. Otherwise, they won’t know what the final sentence will be. Is your city “Paris” or is it “crowded”?

Note that the translator can do anything with this string, as long as the translated version contains the %s. For example, they could place it at the beginning of the sentence, which may be the logical flow for some languages.

A string with multiple variables might look like this:

printf(

/* translators: 1: Name of a city 2: ZIP code */

__( 'Your city is %1$s, and your zip code is %2$s.', 'my-plugin' ),

$city,

$zipcode

);.pot, .po, And .mo Files

Great, you know the most important functions for internationalizing your code, but how does it really work? Isn’t that what this guide is for?! Yes it is, and you’re going to learn it, but we have to start with the mysterious translation files.

Note that we’re now shifting from internationalization (making code translatable) into localization (translating).

POT Files

The Portable Object Template file is the template you’re going to give to translators. It’s generated automatically. There are many tools to do that, but the WordPress way is to use WP-CLI “wp i18n make-pot” command. This command parses all of the files in your plugin or theme directory and generates a POT file with all the strings wrapped in i18n functions.

Here’s the post-reading-time.pot file generated by this command now, when our plugin is not yet internationalized:

# Copyright (C) 2025

# This file is distributed under the same license as the Post Reading Time plugin.

msgid ""

msgstr ""

"Project-Id-Version: Post Reading Time\n"

"Report-Msgid-Bugs-To: https://wordpress.org/support/plugin/post-reading-time\n"

"Last-Translator: FULL NAME <EMAIL@ADDRESS>\n"

"Language-Team: LANGUAGE <LL@li.org>\n"

"MIME-Version: 1.0\n"

"Content-Type: text/plain; charset=UTF-8\n"

"Content-Transfer-Encoding: 8bit\n"

"POT-Creation-Date: 2025-08-27T12:18:32+00:00\n"

"PO-Revision-Date: YEAR-MO-DA HO:MI+ZONE\n"

"X-Generator: WP-CLI 2.12.0\n"

"X-Domain: post-reading-time\n"

#. Plugin Name of the plugin

#: post-reading-time.php

msgid "Post Reading Time"

msgstr ""PO Files

Portable Object files are just the filled out templates. The translator gets a POT file, translates all the strings, and saves it as a .po file. Here’s what the translation of our current ‘Post Reading Time’ plugin looks like (only the relevant part):

#. Plugin Name of the plugin

#: post-reading-time.php

msgid "Post Reading Time"

msgstr "Czas Czytania Wpisu"This file would then be saved as post-reading-time-pl_PL.po. The filename format is {text-domain}-{locale}.po.

MO Files

The MO files are compiled PO files. These use a binary format which makes them more efficient. Once again, you can compile your .po files into .mo files using different tools. The most fundamental one is the gettext’s msgfmt command. For us, that’d be:

msgfmt -o post-reading-time-pl_PL.mo post-reading-time-pl_PL.poThe PO filenames really didn’t have to abide by the {text-domain}-{locale}.po format, but the MO files do because that’s how they are found and loaded by WordPress.

Loading The MO Files

You’ve internationalized your code, you translated it, and you generated the .mo files. That’s great, but WordPress has no idea about them until you load them. There are a few ways of achieving that, and a couple of nuances to keep in mind.

PS: This process is very different for themes and plugins hosted on wordpress.org. There’s an entire section on that later on.

load_plugin_textdomain() & load_theme_textdomain()

Let’s assume we created a /languages subdirectory for our plugin. The path to that directory would be /wp-content/plugins/post-reading-time/languages. This folder would contain all our .mo files. The first way of loading those translations would be explicitly calling load_plugin_textdomain(). Here’s an example:

function pgn_load_translations() {

load_plugin_textdomain(

'post-reading-time',

false,

dirname( plugin_basename( __FILE__ ) ) . '/languages'

);

}

add_action( 'init', 'pgn_load_translations' );The first argument is the text domain, the second one is deprecated (just make it false), and the third one is the path relative to the /wp-content/plugins/ directory. WordPress will then load all the MO files in this directory with the matching text domain in the filename.

By the way, there’s also load_theme_textdomain() and load_child_theme_textdomain().

Domain Path

So that was your first option – explicitly calling a PHP function. The second option is with a ‘Domain Path’ header comment. You have to place this comment either in styles.css (for themes) or in the plugin’s main file (for plugins). The value of that parameter is the relative path to the directory containing MO files. Example:

/*

* Plugin Name: Post Reading Time

* Domain Path: /languages

*/WordPress will automatically find and load all your MO files in this folder. No explicit function call is needed.

I’ve mentioned that there are a couple of nuances to keep in mind. Here’s the first one. load_plugin_textdomain() and ‘Domain Path’ are not really the same. If you only load your MO files explicitly without specifying the ‘Domain Path’, then your plugin/theme metadata won’t be translated.

Think about it. We translated our plugin’s name from English “Post Reading Time” to Polish “Czas Czytania Wpisu”. What happens when the user disables the plugin? Our code won’t run and the translations won’t be loaded, yet the name will still be displayed in the admin dashboard.

If you specify ‘Domain Path’, the MO files will always be loaded, even if the plugin is disabled. That’s why it’s usually better to use ‘Domain Path’ instead of load_plugin_textdomain().

Text Domain

There’s one more header comment relevant to translations and it’s a source of more complex nuances. The header in question is ‘Text Domain’. This property, as you might have guessed, specifies the text domain of your theme/plugin. Example:

/*

* Plugin Name: Post Reading Time

* Text Domain: post-reading-time

* Domain Path: /languages

*/Here’s the tricky part: it’s not always needed. First of all, it’s not required if you load your MO files with load_plugin_textdomain() because this function expects the text domain as its first parameter. The situation is a little different if you’re using ‘Domain Path’.

When auto-loading translations with ‘Domain Path’, the ‘Text Domain’ is required if your text domain doesn’t match your theme’s or plugin’s slug. What is a slug? In practice, it’s just the name of your main folder.

For our plugin located at /wp-content/plugins/post-reading-time/, the slug is “post-reading-time”. That’s why I used this awfully long text domain in all the i18n function calls – it’s recommended to always use the slug as your text domain.

If your text domain was different from the slug (e.g., “pgn-reading-time”), then you’d have to specify it with “Text Domain: pgn-reading-time”. Otherwise, the MO files wouldn’t be loaded, even if you defined the Domain Path.

Inner Workings Of The Translation System

You’ve seen the “what” of translations. You know how to internationalize your code, you know how to translate it, and you know how to load the translations. It’s time for you to understand the “how” behind this entire system.

The first step WordPress takes is determining what language to use. It usually does this by reading the WPLANG option (from the wp_options table). This option stores the active locale (e.g., en_US, pl_PL, fr_FR, etc.). This locale can be set in Settings.

Next, the appropriate MO file is loaded. The expected filename is computed, i.e., {text-domain}-{locale}.mo. If this file is found, it is parsed and loaded into memory. Remember that .mo files are just binary files containing the original string and its translated version.

The i18n functions, like __(), start by getting the appropriate Translations object. They get it from a global array of all loaded translations: $l10n. This is an associative array where the key is the text domain and the value is the object.

Every Translations instance contains an associative array of all translated strings where the original string is the key and the translated string is the value, like:

public $entries = array( $msgid => $msgstr );That’s a map of all the original hard-coded strings and all of their translations. Getting the translated value returned by __() is as simple as doing $entries[$msgid]. This class is defined in /wp-includes/pomo/translations.php if you want to have a look.

Code Example

Now that you understand how this system works, let’s translate our Post Reading Time plugin to Polish as an example.

Internationalization

We’ll start by internationalizing it, which means wrapping all strings in i18n functions. We’ll walk through it step by step.

function pgn_add_snippet_to_post_content( $content ) {

if ( ! is_single() || ! is_main_query() || ! in_the_loop() ) {

return $content;

}

$reading_time_text = get_option( 'pgn_reading_time_text' );

if ( empty( $reading_time_text ) ) {

$reading_time_text = __( 'Reading time', 'post-reading-time' ); // Default

}

$reading_time = pgn_calculate_reading_time( $content );

$mins_text = _n( 'min', 'mins', $reading_time, 'post-reading-time' );

$display_text = sprintf(

/* translators:

* 1: The label, either default ("Reading time") or user-defined

* 2: The number of minutes

* 3: The word "min" or "mins"

*/

__( '%1$s: %2$d %3$s', 'post-reading-time' ),

$reading_time_text,

$reading_time,

$mins_text

);

$display_html = '<div class="pgn-reading-time">' . $display_text . '</div>';

$display_html = apply_filters( 'pgn_display_html', $display_html, $reading_time_text, $reading_time );

return $display_html . $content;

}There are a couple of interesting things going on here. The first is obvious – the default “Reading time” got wrapped in __(). We’ll now be able to translate the default string. But if you look closer, you’ll see that it’s only used when there was no string stored in the database. How do we translate the user-provided text? We don’t.

There is no way to translate anything in the database, including any options or content, using MO files. That is not their job. Their job is translating hard-coded strings. We’ll talk about translating content later.

The next one after the default reading text is $mins_text. We use the _n() pluralization function to be able to use a different word depending on the number of minutes (“min” vs “mins”). In this case, we made the ‘mins’ a separate variable because of how the final text is created.

The display text uses sprintf() with 3 variables: the label, the number of minutes, and the pluralized ‘mins’. As you can see, we also included a much needed comment for the translators, explaining what those variables are.

function pgn_text_section_html() {

echo '<p>' . __( 'Settings related to text', 'post-reading-time' ) . '</p>';

}

function pgn_settings_init() {

// First is $option_group, second is $option_name (the one stored in the database)

register_setting( 'pgn_post_reading_time_group', 'pgn_reading_time_text' );

add_settings_section(

'pgn_text_section', // $id - unique ID of the section

__( 'Text Settings', 'post-reading-time' ), // $title - displayed as heading

'pgn_text_section_html', // $callback

'pgn_post_reading_time_menu' // $page - slug of our menu page

);

add_settings_field(

'pgn_reading_time_text', // $id

__( 'Text alternative to "Reading time"', 'post-reading-time' ), // $title - label

'pgn_reading_time_text_html', // $callback

'pgn_post_reading_time_menu', // $page

'pgn_text_section' // $section

);

}

function pgn_annoying_welcome_message() {

$text = __( 'Thank you for downloading my plugin!', 'post-reading-time' );

echo '<div class="notice notice-info is-dismissible"><p>' . $text . '</p></div>';

}These two are just simple __() calls so I bundled them together. Nothing fancy or new here. You can see that we’re internationalizing only the user-facing strings.

function pgn_settings_page_init() {

add_options_page(

__( 'Post Reading Time Settings', 'post-reading-time' ), // $page_title - displayed in <title>

_x( 'Post Reading Time', 'settings submenu title', 'post-reading-time' ), // $menu_title

'manage_options', // $capability - don't worry about that now

'pgn_post_reading_time_menu', // $menu_slug - slug & unique ID

'pgn_settings_page_html' // $callback

);

}Last but not least, we use _x() for the submenu name, giving the string context. I did that mostly for demonstration purposes, but you could argue that the string “Post Reading Time” might be translated differently for the frontend, the plugin’s name, and the submenu. This ensures that we can have a separate translation for the name of the submenu leading to our settings page.

Generating The POT File

Let’s now head to our plugin’s directory and run “wp i18n make-pot .”. This will create a “post-reading-time.pot” file. Next, create the /languages directory and move this POT file there. Here are the contents of this file (minus the metadata at the top):

#. Plugin Name of the plugin

#: post-reading-time.php

msgid "Post Reading Time"

msgstr ""

#: post-reading-time.php:38

msgid "Reading time"

msgstr ""

#: post-reading-time.php:42

msgid "min"

msgid_plural "mins"

msgstr[0] ""

msgstr[1] ""

#. translators: 1: The label, either default ("Reading time") or user-defined 2: The number of minutes 3: The word "min" or "mins"

#: post-reading-time.php:50

#, php-format

msgid "%1$s: %2$d %3$s"

msgstr ""

#: post-reading-time.php:65

msgid "Settings related to text"

msgstr ""

#: post-reading-time.php:80

msgid "Text Settings"

msgstr ""

#: post-reading-time.php:87

msgid "Text alternative to \"Reading time\""

msgstr ""

#: post-reading-time.php:113

msgid "Post Reading Time Settings"

msgstr ""

#: post-reading-time.php:114

msgctxt "settings submenu title"

msgid "Post Reading Time"

msgstr ""

#: post-reading-time.php:123

msgid "Thank you for downloading my plugin!"

msgstr ""You can see that most of those entries are just simple key-value pairs with a comment at the top showing their origin. The msgid is the original string, and we’ll fill msgstr later when translating. The first deviation is this:

#: post-reading-time.php:42

msgid "min"

msgid_plural "mins"

msgstr[0] ""

msgstr[1] ""That’s the entry for our _n() call. msgstr[0] is the singular translated string, and msgstr[1] is the plural one. There’s another interesting entry right after:

#. translators: 1: The label, either default ("Reading time") or user-defined 2: The number of minutes 3: The word "min" or "mins"

#: post-reading-time.php:50

#, php-format

msgid "%1$s: %2$d %3$s"

msgstr ""That’s how translators will see our comments. Now try to translate this msgid without it. Good luck. You can also see the “php-format” hint, indicating that we’re using the sprintf function.

#: post-reading-time.php:114

msgctxt "settings submenu title"

msgid "Post Reading Time"

msgstr ""And here’s the _x() call. The context is stored as msgctxt. We’re still only translating the msgstr, but the context makes it separate from other msgid equal to “Post Reading Time”. One such entry was the plugin name at the very top of the file.

As a matter of fact, if we replaced this _x() call with a __() call, this entry would cease to exist. It would be merged with the plugin name, as the msgid (the original string) is exactly the same. Think back to how translations are stored in memory. For _x(), the key searched for in the array is actually “{msgctx}\4{msgid}”, so it’d be “settings submenu title\4Post Reading Time” (\4 is a special ASCII EOT character).

Localization

It’s time to create the PO file with the final translations. Let’s start by translating the boring part – the __() and _x() strings. They are just a simple string. After that, we’ll take care of mins and the display text with variables. Remember to leave the .pot file as is. Make a copy of it named “post-reading-time-pl_PL.po”.

#. Plugin Name of the plugin

#: post-reading-time.php

msgid "Post Reading Time"

msgstr "Czas Czytania Wpisu"

#: post-reading-time.php:38

msgid "Reading time"

msgstr "Czas czytania"

#: post-reading-time.php:65

msgid "Settings related to text"

msgstr "Ustawienia związane z tekstem"

#: post-reading-time.php:80

msgid "Text Settings"

msgstr "Ustawienia tekstu"

#: post-reading-time.php:87

msgid "Text alternative to \"Reading time\""

msgstr "Alternatywa dla \"Czas czytania\""

#: post-reading-time.php:113

msgid "Post Reading Time Settings"

msgstr "Ustawienia Czasu Czytania Wpisu"

#: post-reading-time.php:114

msgctxt "settings submenu title"

msgid "Post Reading Time"

msgstr "Czas Czytania Wpisu"

#: post-reading-time.php:123

msgid "Thank you for downloading my plugin!"

msgstr "Dziękuję za zainstalowania mojej wtyczki!"Localizing ‘mins’

The boring part’s done, it’s time to tackle the more interesting translations. Let’s start with translating the pluralized ‘mins’ string. We could do something like that:

#: post-reading-time.php:42

msgid "min"

msgid_plural "mins"

msgstr[0] "minuta"

msgstr[1] "minuty"That would give use “1 minuta”, “2 minuty”, etc. But there’s a huge problem. The Polish language, along with many other languages, has two different forms for the plural phrase… There’s “2, 3, 4 minuty”, and there’s “5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 minut”. There are also exceptions, like the fact that for numbers 12, 13, and 14, the correct form is “minut”, while for other number ending with 2, 3, and 4 (like 22, 23, 24), the correct form is “minuty”. Here is the logic written in pseudocode:

if ( number == 1 ) return “minuta”

else if ( number.last_digit IN (2, 3, 4) AND number.last_two_digits NOT IN (12, 13, 14) ) return “minuty”

else return “minut”

So how do you achieve that? Thankfully, the creators of gettext thought of that and introduced a special ‘Plural-Forms’ header. This header allows you to specify the number of plural indexes and a formula. Here’s the header for Polish PO files:

"Plural-Forms: nplurals=3; plural=(n==1 ? 0 : n%10>=2 && n%10<=4 && (n%100<10 || n%100>=20) ? 1 : 2);\n"This achieves exactly the same thing as our pseudocode. Don’t worry, you don’t have to come up with that yourself. Every language has specified rules and you can easily find the correct formula for each of them. Thanks to this header, all _n() entries can now have 3 indexes, and the right one will be chosen according to the formula. Here’s the final translation:

#: post-reading-time.php:42

msgid "min"

msgid_plural "mins"

msgstr[0] "minuta"

msgstr[1] "minuty"

msgstr[2] "minut"PS: Because the _n() function only accepts a singular and plural argument, there is no way for you to use a language with 3 plural forms as the original language.

Localizing sprintf() Display Text

This one is going to be a breeze compared to _n(). Let me remind you of what we’re working with:

#. translators: 1: The label, either default ("Reading time") or user-defined 2: The number of minutes 3: The word "min" or "mins"

#: post-reading-time.php:50

#, php-format

msgid "%1$s: %2$d %3$s"

msgstr ""Here’s the thing – we could really leave it as is. Because there is no static text in this string, there’s nothing for us to translate. All of the variables – the default text and the ‘mins’, have already been translated. They will only get inserted into this string.

The one thing we can do is change the order of the variables. In this case, it doesn’t make any practical sense. The reading order in Polish is exactly the same as it is in English, so in reality, we’d just leave it. That being said, let’s mess it up a bit for demonstration purposes:

#. translators: 1: The label, either default ("Reading time") or user-defined 2: The number of minutes 3: The word "min" or "mins"

#: post-reading-time.php:50

#, php-format

msgid "%1$s: %2$d %3$s"

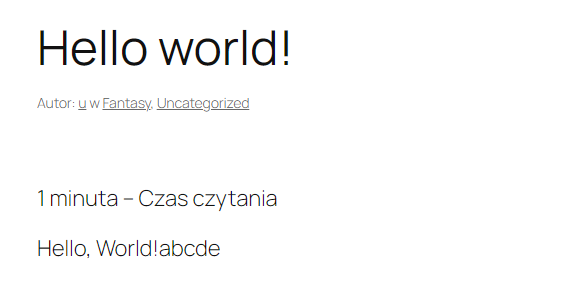

msgstr "%2$d %3$s - %1$s"Now, instead of the string being “Czas czytania: 1 minuta”, it’ll be “1 minuta – Czas czytania”. Notice that we’re completely free to rearrange the flow of the sentence and delete, add, or modify any other static text – in this case, replacing the colon (:) with a hyphen (-).

Compiling & Loading The MO File

Now that we have the fully translated PO file, it’s time to compile it and load it. You already know how to do that. Head to the /languages folder and execute:

msgfmt -o post-reading-time-pl_PL.mo post-reading-time-pl_PL.poThen modify the main plugin file’s header to include:

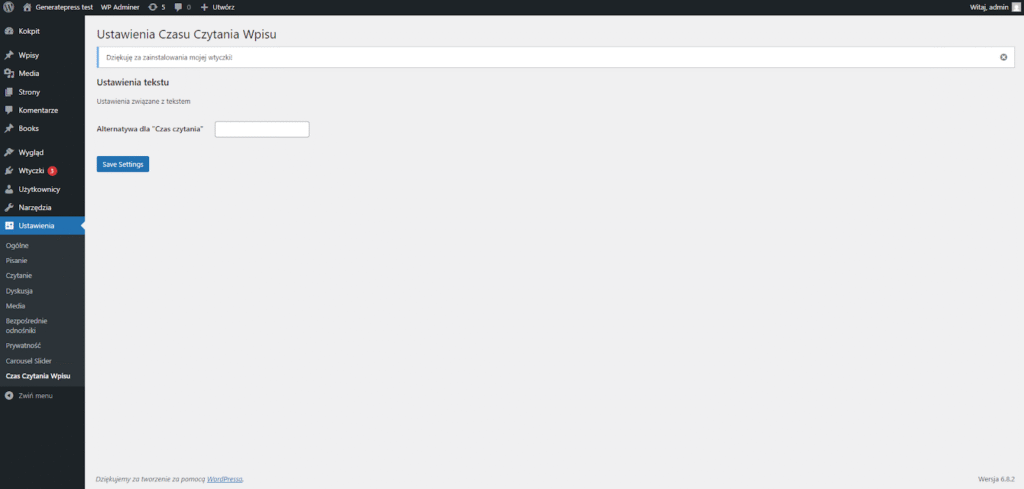

// Domain Path: /languagesThat’s it. Our translation file should now be loaded. You should see them if you change your language to Polish in Settings. Here’s our translated settings page:

And here is the frontend of a post: