Block themes are themes built entirely out of blocks. They are the future of WordPress, but they have their own problems. To understand block themes, we have to first understand why they exist in the first place.

Blocks Themes vs Classic Themes

Think about what it’s like to customize a classic theme. Want to change an option? You go to the Customizer. Want to create a menu? You go to Appearance > Menus. Want to add a piece of content in some place? You create a widget. Want to write a post? You write the post in the editor (potentially using shortcodes). Want to modify a template or a template part? Go write some PHP in a child theme. The experience is inconsistent and confusing. Block themes are supposed to solve that.

The underlying concept block themes are meant to enable is Full Site Editing (FSE). FSE is the idea that you can edit every part of your website in a consistent manner – no matter if it’s a menu, page content, or a template. This is achieved by making everything a block. If all parts of your website are wrapped around the same abstraction (a block), you can treat them uniformly and provide a consistent experience.

Block Theme Structure

The structure of a block theme is a little different. The most important change is that templates have to be placed in the /templates folder, and template parts have to be placed in the /parts folder. There’s also a new, very important file – theme.json. All the other rules still apply. You have to have a style.css file and you can create a functions.php file.

Templates & Template Parts

Templates is where the first major difference becomes apparent. Templates in classic themes were PHP files (.php). Templates in block themes are HTML files (.html). These files do not contain the final HTML markup. They contain block syntax. Remember the Code editor view of the Block Editor where you could see the block delimiters? That’s what’s in those files.

The template hierarchy is the same for both types of themes. The only difference is that WordPress searches for templates in the /templates directory instead of the root theme directory. WordPress knows that a theme is a block theme by checking if the /templates/index.html file exists. If it does, it’s a block theme.

Template parts share the same characteristics as templates – they contain block markup and are searched for in the /parts directory. Parts aren’t included using functions because there are no functions in HTML. Instead, there’s a template part block:

<!-- wp:template-part {"slug":"header"} /-->This block will get replaced with the contents of the /parts/header.html file. The slug attribute specifies the name of the file without the file extension.

If you remember the section about Synced Patterns, then you might think they are pretty similar to parts. You wouldn’t be wrong. The only difference between the two is the fact that parts are primarily file-based, and Synced Patterns are stored only in the database.

There are, however, many internal talks about allowing Synced Patterns to be registered by themes (with files) instead of only by users. It’s also discussed to merge the concepts of patterns and template parts into one. As a matter of fact, template parts are available under the “Patterns” menu in the Site Editor, and here’s what the footer.html template part looks like in the Twenty Twenty Five theme:

<!-- wp:pattern {"slug":"twentytwentyfive/footer"} /-->Note that this is a normal (not synced) pattern. This means it literally includes the pattern’s block markup in the parts/footer.html file, which is then included in the template files. More on theme-registered patterns later.

Customizing Templates and Template Parts

Remember how I said the template hierarchy for block themes is the same as for classic themes? I lied. Block themes have another layer to the template hierarchy – the database.

For Full Site Editing to be useful, the user needs to be able to modify the templates. That’s pretty obvious. But we’ve already learned that if you modified the actual template files, they’d be overwritten on the next theme update. That’s where the database comes in.

Block themes allow users to modify templates in the Block Editor, just as you would write a post. This functionality is available in the Site Editor (explained later). You can literally do anything – add/remove a block, change block settings, or even build the template from scratch.

Such user-created templates are saved to the database as posts, where the post_content is the markup of the entire template (it’d be exactly the contents of the .html file if you didn’t change anything). The post_type is either wp_template or wp_template_part (yes, you can modify template parts as well).

The templates and template parts in the database take priority over their file-based counterparts. This is like child themes for classic themes, except it’s a layer above. The order of the template hierarchy for block themes looks like this:

- Database

- Child theme (if active)

- Parent theme

Creating Templates and Template Parts

Let’s say you wanted to create a theme for distribution. You could write all of your templates by hand, but that’s stupid. You’re going to make a mistake writing the block delimiters, you’ll have to constantly look up the correct syntax, and it’ll be painfully slow. A better way is using the Block Editor.

You already know the power of the Block Editor – you can create the block markup from a graphical interface. But you’ve also already learned that templates created this way get saved in the database, not in files, and you certainly can’t give someone your database if you want them to install your theme.

In reality, you’d create your templates in the Site Editor and then manually copy the generated markup to your template files or use the built-in export functionality. Alternatively, you could use the official Create Block Theme plugin. This plugin is more complex, and allows you to export not only templates but other modifications stored in the database as well. You should check it out if you’re planning on creating and distributing a block theme.

Custom Templates

We’ve already talked about custom templates in the classic themes section. They were called ‘Page Templates’ back then. The idea in block themes is the same. You create a template that the user can manually choose for a post/page. This chosen template is then at the top of the template hierarchy.

The difference between custom templates in block themes and classic themes (except obviously for the file type) is how they are registered. With custom themes, you had to put a comment in the PHP file. With block themes, you have to register the template (the HTML file) in the theme.json file. We’ll talk about it more when covering this mysterious file.

Just like normal templates, users can create new or overwrite custom templates in the Site Editor. This version will be stored in the database with post type wp_template and will have priority over the file.

Patterns

We’ve already talked about Block Patterns while discussing blocks. We didn’t go into much detail back then, only what they are (pre-arranged groups of blocks), types of patterns (synced vs not synced) and how to register them. This section is focused on the more concrete ways of using patterns when building websites and themes.

Patterns in block themes are usually registered by placing them in the /patterns directory. As explained in the aforementioned section, the metadata about the pattern is provided in the header comment. These patterns are PHP files. Note that they can only be normal (not synced) patterns. Registering synced patterns by themes is not possible (for now).

Why are patterns PHP files and not HTML files? Well, there are a couple of benefits to using PHP:

- Strings become translatable (crucial for hard-coded, theme specified strings).

- You can use PHP functions and dynamic data.

- You can specify the options in a PHP comment for WordPress to auto-register the pattern.

Unlike templates and template parts, theme-registered patterns cannot be edited directly by the user. If the user wants to modify a pattern, they have to create a new one by duplicating the one they want to edit.

Using Patterns In Templates

Remember the footer.html template part in the Twenty Twenty Five theme? It used a twentywentyfive/footer pattern as its only content. Let’s look at it again.

<!-- wp:pattern {"slug":"twentytwentyfive/footer"} /-->By the way, the pattern block is only meant to be used in code by theme developers. You will not find it in the visual Block Editor. What this block does is it just loads the pattern registered under the specified name. Note that, because it’s not a synced pattern, it’ll be loaded as a dumb copy. You will not see the wp:pattern delimiter if you switch to the Code editor view. You will see the markup of the pattern.

Let’s assume the footer pattern was a very simple pattern, having only a static image. This is what the /patterns/footer.php source code might look like:

<?php

/**

* Title: Footer

* Slug: twentytwentyfive/footer

* Categories: footer

* Block Types: core/template-part/footer

* Description: Footer with just an image.

*/

?>

<!-- wp:image {"sizeSlug":"full","linkDestination":"none"} -->

<figure class="wp-block-image size-full">

<img src="<?php echo get_template_directory_uri(); ?>/assets/images/sample-image.png"/>

</figure>

<!-- /wp:image -->As you can see, we’re using the get_template_directory_uri() WordPress PHP function to get the URL of the image. This is good, as we wouldn’t be able to do that without PHP. Keep in mind when this code is actually executed.

The PHP code is compiled when the pattern is registered, and that happens on the init hook. At this point, WordPress is yet to have many important properties set up, such as the global $wp_query or $post objects. This means you can’t use functions that depend on that data such as the_content() or is_single() in patterns. The final HTML is compiled now, and only inserted later when using the pattern.

The practical consequence of that is that patterns cannot be used for dynamic, page-specific content. That’s because by the time WordPress gets to handling the specific page, the pattern’s HTML is already rendered and stored in memory.

An interesting side effect of using normal patterns in template files is them acting a little like synced patterns. Just imagine you use some theme-registered pattern in 5 of your templates. If you change the underlying pattern, all of the templates are going to change as well, even though the pattern is not synced.

This happens because the pattern is re-compiled every time the template is rendered from the file. Of course this magic stops working the moment the user modifies the template in the Site Editor, as this saves the rendered HTML in the database.

You can still make it work if you put the pattern block in a template part and the user doesn’t modify the template part itself (like the Twenty Twenty Five theme did with the pattern being placed in the footer template part). Unlike the pattern block, the template part block doesn’t have to be rendered before it gets saved in the database. Think about it for a second, it’s a nice exercise to see if you really understand how block parsing works ;).

Starter Patterns

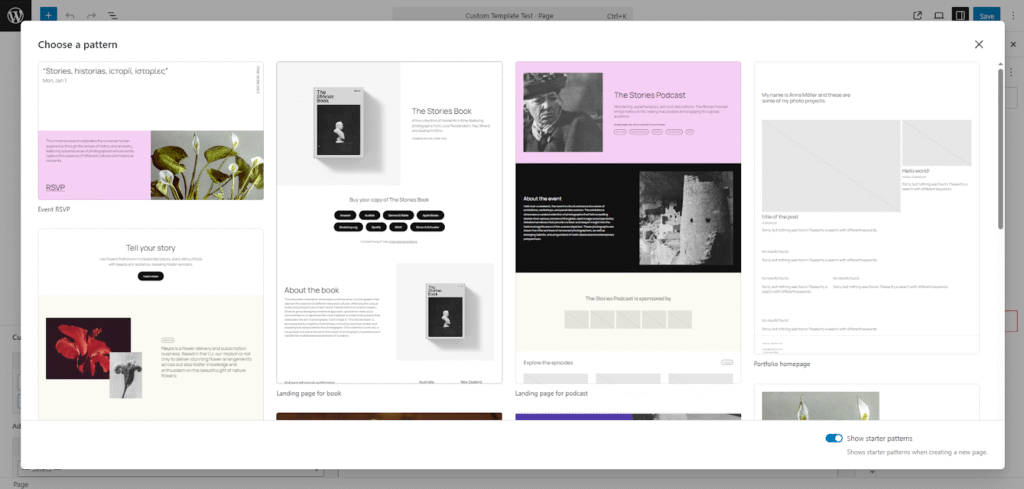

If you create a new page (or post), or the page you open to edit has no content, WordPress will, by default, show you starter page patterns to choose from. These are full, pre-assembled, pre-styled pages that you can add to your page in one click instead of having to start from a blank canvas. Here’s what that looks like:

Any pattern can be registered as a page pattern. It requires a specific set of parameters when registering the pattern (the header comments):

- Block Types – has to contain ‘core/post-content’.

- Post Types – allows you to specify post types for which the pattern will be suggested.

If you do that, your pattern will be displayed in this modal every time a user creates a post of the selected post type(s). Besides starter page patterns, there are also starter template patterns. They work exactly like page patterns, but they are suggested when the user creates a template in the Site Editor (e.g., a single post, an archive, or a front page template).

To make your pattern a template pattern, you have to specify the ‘Template Types’ parameter when registering the pattern. This attribute sets the template types for which the pattern will be suggested, e.g., “index”, “home”, “single”, “singular”, etc.

Block Type Patterns

Block type patterns are patterns linked to a block. This linking is done by using the ‘Block Types’ property. We’ve linked our starter page patterns to the core/post-content block. But what is it? What does it mean to link a pattern to a block?

Linking, or connecting, a pattern with blocks, just means you make WordPress aware that the pattern is meant for the blocks. In practice, that means you can choose to transform a block into this pattern when inserting it.

When you insert a block that has linked patterns, you can click on its icon and choose a pattern. This plain, unstyled block, will then be replaced with the chosen pattern. How does it differ from just using the pattern in the first place? Well, the result is the same.

The power of block type patterns is that you don’t have to remember all of the patterns and search for them. You create some patterns for the grid block, and then you choose the right pattern when inserting a grid – or you don’t choose a pattern at all. A block which benefits a lot from that is the Query Loop block. You can have pre-defined types of loops and just choose the one you want when inserting the block.