Multisite is an advanced WordPress feature. It lets you create multiple “subsites” under the same website (using the same core files and database). It is useful for enterprise-level purposes with multiple teams having to manage their own part of the entire website, e.g., universities, franchises, SaaS products, large blog networks, etc.

Multisite originated from the separate WordPress MU (multi-user) project. It got merged into core in WordPress 3.0. This is why some old functions and hooks are prefixed with “wpmu_”. The two most important terms in Multisite are “site” and “network”. A site is a single site instance with its own content, uploads, etc. A network is the set of all sites. Every site is managed by a site administrator. The network is managed by a network administrator (or super admin).

Multisite works by modifying the database and filesystem structure. Every site in a network has its own content tables (wp_posts, wp_postmeta, wp_terms, etc.), but there are also network-wide tables. All files except for the uploads directory are shared. This means that all sites run the exact same plugins, themes, and core.

Plugins and themes can only be installed and updated by the super admin. Site admins can only choose to enable or disable plugins made available (installed) by the network administrator, unless the network administrator has made them required for all sites. Site admins can also choose to activate one of the themes installed by the super admin.

By default, a Multisite install can be either subdirectory or subdomain-based. A subdirectory-based Multisite exposes individual sites at subdirectories, i.e., example.com/site1. Subdomain-based Multisite does so on subdomains, i.e., site1.example.com. Note that all of these use the same domain (example.com). Since WordPress 4.5, you can modify a single site to use a completely separate domain. This process is called domain mapping.

Database Structure With Multisite

When you configure Multisite on your WordPress install (which we’ll soon do), a few new tables get added to your database. New network-wide tables are:

- wp_site

- wp_sitemeta

- wp_blogs

- wp_blogmeta

- wp_registration_log

- wp_signups

wp_site and wp_sitemeta contain information about networks. Theoretically, a single WordPress Multisite installation can have multiple networks. In practice, this is never used and it’s not supported by default in WordPress (there’s no UI for that). wp_blogs and wp_blogmeta contain information about single sites in a network.

Why is it wp_site and not wp_network? That’s because of Multisite’s history. A network used to be called a site, and a site used to be called a blog. What we now call “sites in a network” used to be called “blogs on a site”. That’s something to keep in mind to not get confused with these naming quirks.

The following tables are specific to every site:

- wp_posts

- wp_postmeta

- wp_terms

- wp_termmeta

- wp_term_relationships

- wp_term_taxonomy

- wp_options

- wp_comments

- wp_commentmeta

- wp_links

Every site in the network gets its own set of these tables. They are named with the ID of the site. The posts table for the site with ID 2 would actually be named wp_2_posts. If you added another site, it would get tables like wp_3_posts, wp_3_postmeta, etc. The first site (created before configuring Multisite) keeps the original tables without the ID.

Do you see anything missing on that list? What about wp_users and wp_usermeta? Well, I got a surprise for you – these are network-wide and shared across all sites. That’s right, a user on one site is also a user on all other sites in the same network. This is so important that I’ve devoted an entire section to it down below.

File Structure With Multisite

The file structure for Multisite is the exact same except for the uploads directory. Every site has its own media library. The directory doesn’t change for the original website (with ID 1) – the files still live under /wp-content/uploads. New sites’ files are organized into site-specific subdirectories. The path is /wp-content/uploads/sites/ID/. A site with ID 2 would store media in /wp-content/uploads/sites/2/.

User Accounts With Multisite

This is perhaps the most interesting and confusing part of Multisite. As I already said, the wp_users and wp_usermeta tables are shared across the entire network. This means that an account created on one site can log into every other site in the network. But there’s a catch – some meta values are scoped to the site by including the ID in the meta key, e.g., wp_2_capabilities.

A user that registers an account on site with ID 2 will have the wp_2_capabilities meta value containing the “subscriber” role. They will, however, not have any value for wp_3_capabilities (this meta key will not be created for the user, even if a site with ID 3 exists). This means that for the site with ID 3, they have absolutely no capabilities. If this site checks if current_user_can() anything – it will return false for this user.

This fact alone doesn’t stop them from logging into the site and acquiring a session. /wp-login.php will indeed log them in, as it doesn’t look at the capabilities but only at wp_users to see if the user with this login and password exists. But if they try to visit /wp-admin/ (which is something even subscribers can do to edit their own details) – they will get a message telling them they don’t have the permissions to do that. They have a session, the global $user is populated, and is_user_logged_in() returns true, but they don’t have any capabilities.

An even more interesting quirk is that site administrators only see users in the users list that have the wp_ID_capabilities meta key for their site. This means that someone can be logged into your site, but if you visit the ‘Users’ tab in the admin panel – you will not see them in the list of all registered users! This can be particularly confusing if your site offers functionality that doesn’t require any capabilities. The user will be able to perform that action and you still won’t be able to see them in the list – like a ghost.

I was curious to see how that worked and set up an experiment. I installed and activated WooCommerce for my entire network. I logged into example.com/site1/ using an account that doesn’t have any capabilities on that site. I headed to /my-account/ and modified my account details. I logged into the main site on example.com with the same account and viewed my details. Sure enough – the details I saw were the ones I set up on the site I didn’t have any capabilities on!

Turns out WooCommerce stores those details in wp_usermeta with the “billing_first_name” and “billing_last_name” keys (and they also update the default “first_name” and “last_name” meta values). Those aren’t scoped to the site with the site ID! They also don’t check for any capabilities on pages that allow you to change your own details.

This means that if you’re running WooCommerce on Multisite, user details set up on one site will be used across the entire network. This is also the case with any other plugin that uses the general built-in user details (e.g., first name, nickname, email, etc.) or any other user metadata that isn’t scoped to the site. That’s certainly something to keep in mind.

PHP Multisite Functions

There are a couple of important Multisite functions and classes you’ll use when writing plugins. The single most important one is probably is_multisite(). This function returns either true or false, depending on if multisite is enabled.

There’s also a peculiar function wp_is_large_network(). It’s used to check if the current network is considered “large”. The default criteria for a large network are either 10,000 sites or 10,000 users (depending on the argument you pass – default is ‘sites’). These numbers can be changed with filters. This function is used in a few places by core – probably for optimization purposes.

One of the most important functions is switch_to_blog(). This function lets you switch the context from the current site to another site in the network (you pass its ID). The only two things it does underneath is change the database prefix (i.e., from “wp_2_” to “wp_3_”) and change the Object Cache prefix (some Object Cache entries are automatically scoped to the site by prefixing the key with the blog ID). You have to remember to always call restore_current_blog() afterwards, which reverts these changes.

switch_to_blog() isn’t very useful unless you couple it with something like get_sites(). This function lets you query for sites. You can, for example, fetch a list of all site IDs in the network and iterate over them. Inside the loop, you can call switch_to_blog() and display some information about this blog with get_bloginfo() or some posts with WP_Query or get_posts().

You can also create a new site programmatically. wp_insert_site() inserts the site and its information into the wp_blogs table. After this is done, you have to call wp_initialize_site(). This runs the initialization routine for the site – including creating all the database tables. You can use those if you want to create a custom UI for adding sites by users (useful for SaaS).

get_site_option() and update_site_option() let you get and update options stored in wp_sitemeta. This is the network-wide metadata table. It really functions like wp_options but for the entire network. Since WordPress 4.4, these functions are wrappers over get_network_option() and update_network_option(). These are more semantically correct – you can use them directly if you’re not planning on supporting <4.4. They default to get_option() and update_option() if multisite isn’t enabled, so you can safely use them without checking if is_multisite().

How Other Functions Are Affected By Multisite

Multisite is probably the single most important reason why you should always use the built-in WordPress functions and APIs. You hard-coded the path to /wp-admin/ in your code? Guess what – if someone sets up a site at example.com/site1/, their wp-admin will live at example.com/site1/wp-admin/ and your code will break. That’s exactly why I’ve been preaching the use of built-in URL and path functions this whole time. They take care of that for you.

Naturally, all database-related functions are indirectly affected by Multisite. This is because the global $wpdb object has the table prefix scoped to the site. Yet another reason to use the built-in APIs. The Object Cache also scopes your entries (the cache key) to the site, unless the group you’re adding the entry into is global. You register a group as global with wp_cache_add_global_groups(). If that’s the case, the cache key will be the same across the entire network. Some default global groups are users, user_meta, theme_files, sites, networks and more.

When To Use Multisite

Multisite shines when:

- you want one WordPress installation to manage multiple sites with shared code (plugins, themes, and core),

- you want shared user accounts across sites,

- the sites are intrinsically linked together (one displaying content from another),

- you want to scale site creation (deploying a new site with the same theme and plugins is much easier than installing and configuring a new WordPress instance).

Multisite is great for when you have many subsites that are somehow related to each other. Imagine a university website, where each department needs to have their own subsite. You can also use it for some SaaS products. WordPress.com is probably the largest multisite network out there. It’s a commercial managed hosting service run by Automattic. Every website hosted on WordPress.com is a site in the network (although it’s far from default Multisite because of its scale).

Multisite breaks down when:

- the websites have wildly different requirements,

- you need isolation of data and resources,

- the individual site admins need to have full control over their websites (installing plugins, themes, etc.),

- you’re not sure if Multisite is a good idea.

In general, Multisite is not a good idea. Use it only if you’ve analyzed your case and decided otherwise. It adds complexity and reduces robustness. First of all, you have one database that houses all the data. What if one site gets hacked? The hacker has access to the entire database – including all the data from the other sites. The same thing is obviously also applicable to files on the disk. This is the main reason why it’s usually stupid to use Multisite to host websites for different clients.

The resources are shared across the entire site. If one site gets DDoSed, the entire network goes down. If one site hogs the database connection, no other site in the network can reach the database. The fact that you’re hosting multiple websites with the same database inherently increases the stress it’s going to have to endure. Don’t choose Multisite if you can’t afford to have that happen.

If you need vastly different plugins on different sites in the network, it’s usually a sign that you shouldn’t be using Multisite. You’re going to have to install all of the plugins for the entire network. The individual site admins will then pick the ones they want to enable. Can you imagine being the site admin and having 100 inactive plugins because they are needed by other sites in the network? And let’s not forget that a vulnerability or a critical error in one plugin can take down the entire network.

Configuring Multisite

The following is just a quick overview of the process of configuring (and managing) a Multisite installation. Read the official WordPress Multisite documentation before you do it yourself.

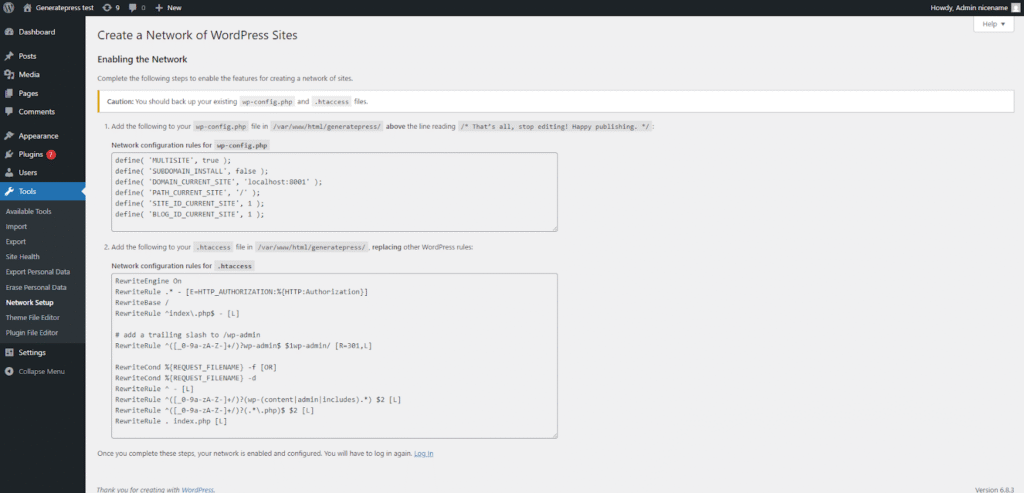

Multisite can’t be enabled when installing WordPress. It can only be activated after the fact. To do it, you have to add “define( ‘WP_ALLOW_MULTISITE’, true );” to your wp-config.php. When you do that, a new menu tab called “Network Setup” will appear under Tools. Here’s what you’ll see when you click it:

As you can see, you’re given the choice to configure the name of the network and the email address of the super admin. This screenshot is from a localhost installation which forces the use of subdirectory. If it was a typical website, you’d also be able to select between a subdirectory and subdomain.

Note that, if your website is over 1 month old, you will be forced to select subdomain to prevent clashes between your new site directories and existing pages. If you’re thinking “this is stupid” – I’m with you. The absurdity of measuring the likelihood of URL clashes with time since WordPress was installed is incomprehensible to me. Thankfully, you can change it later (at least the documentation says so).

After you click “Install”, WordPress will give you code snippets you have to paste in wp-config.php and .htaccess. After doing that, Multisite will be enabled.

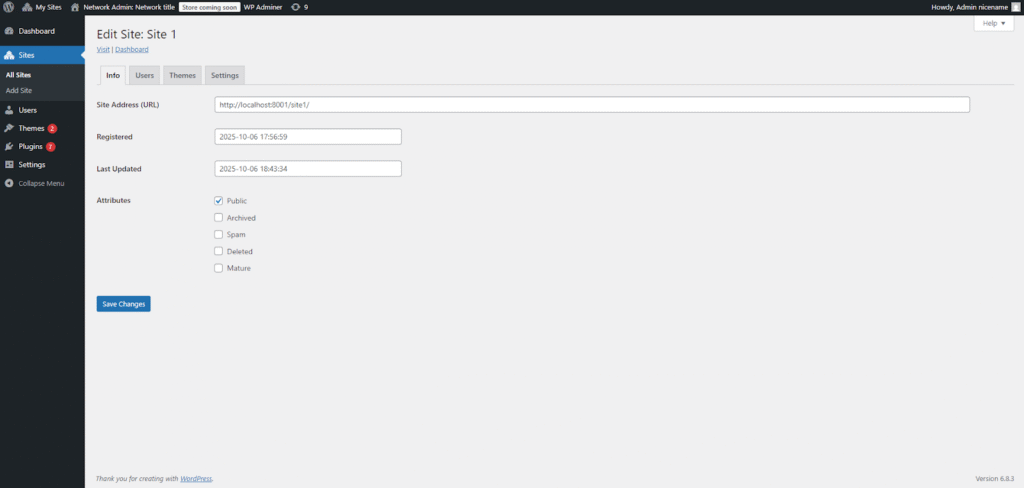

You will immediately see that your dashboard changes. The most important thing is that you’ll be redirected to example.com/wp-admin/network/. This is the URL under which you can manage your entire network. If you visit example.com/wp-admin/, you will get back to the site-specific dashboard for your “original” site (with ID 1 in the network).

You can add sites by navigating to Sites > Add Site, manage users by navigating to Users, enable plugins or themes in Plugins or Themes, and configure network-wide settings in Settings. Every single site has four tabs: Info, Users, Themes, and Settings. You can use them to configure this site as a super admin. A typical WordPress admin dashboard is available to site admins (and you) under /site1/wp-admin/.

PS: If you choose subdirectory instead of subdomain, your posts permalinks structure will suck. It will be prefixed with “/blog”, so you’ll get /blog/post-name/ instead of just /post-name/. I’ve seen some solutions online, but I wasn’t able to get them to work in WordPress 6.8.3.

Plugin Compatibility With Multisite

Not all plugins are compatible with Multisite. Similarly to security, the biggest reason for incompatibility is lack of competence. Some plugin developers don’t know what Multisite is or how it works, and they don’t even know that they need to make their plugins compatible. That’s why you should pay attention to this chapter, even if you aren’t planning on enabling any Multisite installations.

Most WordPress functions just work out of the box. This is particularly true if you’re using built-in APIs. I’ve already addressed how functions’ behaviors change with Multisite. The biggest problems with plugins on Multisite are logic-related. When writing your plugin, you have to constantly keep asking yourself “how should this work on Multisite?”. I’ll name a few examples you should look out for, but this list will not be comprehensive. Do your own reading and thinking when writing a plugin.

Let’s start with one of the most common requirements from a plugin – a menu page. Remember how we added a custom menu page to the admin panel to modify the plugin settings? How should that work on Multisite? Should the page be available in the networks dashboard or in the site dashboard? You have to think about it and use the appropriate hook to add the page.

Let’s assume you want the menu to be added only to the network dashboard. You should probably set the “Network: true” header in your plugin’s main file to make it impossible for site admins to enable it. But if you’re doing that and you want your plugin’s configuration to be global to the entire network, then you should store the settings in wp_sitemeta. Well, guess what, the Settings API doesn’t support that and will store it in wp_options of your site with ID 1. This will make them inaccessible by default on other sites. You have to deal with that.

Let’s say you figured that out. Your options are stored in wp_sitemeta. Now you have to remember that you can’t use get_option() to fetch them. You have to use get_site_option() to get and update_site_option() to update them.

But what if your plugin was activated and configured before Multisite got enabled? I’m assuming you fell back to the normal admin menu page when is_multisite() was false. Your configuration is stored in wp_option, and suddenly, the website administrator enables multisite. Your get_site_option() calls worked before (since they default to get_option() if multisite is disabled), but now they’re checking wp_sitemeta which is empty. Guess what? You have to deal with that yourself 🙂

And did I mention custom database tables? That’s where real fun starts. Let’s say you created a table named “{$wpdb->prefix}table” on the activation hook. The prefix will be scoped to the site. When a site admin on site with ID 2 activates this plugin, a table called “wp_2_table” will be created. Every site will get its own table, which you might or might not want.

But there’s a catch – what if the plugin is network-activated (by the super admin, enforced for all sites)? The activation hook will run only once, and in the context of the site with ID 1. Only one table will be created – “wp_table”. Even worse, your code that queries “{$wpdb->prefix}table” will only work on the main site, as all other subsites will try to query “wp_{ID}_table”, and this table will not exist. If you need site-scoped tables, you have to manually iterate over all sites and create them in the activation hook if it’s activated network-wide (this information is passed as an argument to the activation hook).

And even that is not enough. What if the super admin adds a new site after they’ve already network-activated your plugin? The activation callback will not run for this site and its table won’t be created. You have to hook into wpmu_new_blog and create it. By the way, use $wpdb->base_prefix if you want the table to be global (not scoped to the site with its ID).

There are probably other edge cases you’ll come across as you develop your plugins. The most important thing is to stay vigilant and constantly analyze your logic and how it should work on Multisite (unless you just say “screw it” and not support it). Oh, and test your damn plugins! Multisite can be the source of many weird bugs.